People Who Want Zimbabwe to Become Rhodesia Again

T here was no single moment when I began to sense the long shadow that Cecil John Rhodes has cast over my life, or over the university where I am a professor, or over the ways of seeing the earth shared past then many of u.s. nevertheless living in the ruins of the British empire. But, looking dorsum, it is clear that long earlier I arrived at Oxford as a student, long earlier I helped establish the university's Rhodes Must Autumn motion, long earlier I fifty-fifty left Zimbabwe every bit a teenager, this man and everything he embodied had shaped the worlds through which I moved.

I could start this story in 1867, when a boy named Erasmus Jacobs establish a diamond the size of an acorn on the banks of the Orange river in what is now South Africa, sparking the diamond blitz in which Rhodes first made his fortune. Or I could commencement it a century later, when my grandfather was murdered by security forces in the British colony of Rhodesia. Or I could start it today, when the infamous statue of Rhodes that peers downwards on to Oxford'due south high street may finally be on the verge of being taken down.

But for me, information technology starts about directly in Jan 1999, when I was 12 years erstwhile. That was when my parents first drove me from our home on the outskirts of the city through the imposing black gates of St George's Higher, Harare. Dressed in a red blazer, red-and-white striped tie, khaki shirt and shorts, grey articulatio genus-high socks and a cartoonishly floppy blood-red chapeau, I looked like an English language schoolboy on safari. As our automobile climbed towards the college, I peered up in awe at the granite castle belfry, crowned with a full set of crenellations, that dominates the grounds. It was every bit if I had entered one of the terminal redoubts of Britain'due south global imperium.

Saints, equally I would learn to call information technology, is amongst the oldest and most prestigious schools in Zimbabwe. Information technology was founded in 1896, just five years after the British S Africa Company colonised the inland region of southern Africa north of the Limpopo river. The colonists dubbed the surface area Rhodesia, in honour of the company's founder, Cecil Rhodes. Backed by the British regular army, Rhodes's colonising forces dispossessed millions of Africans of their land and created an apartheid state that endured for 90 years. Saints was established in the mould of the University of Oxford and public schools like Eton to prepare immature white Rhodesians to bear on the country's political and economic regime. For nearly a century information technology was devoted to educating the scions of the land's wealthy white settlers.

Offset in 1963, the college had also accepted a handful of boys from the country's small Black upper class, and afterward a fifteen-year liberation war that won Zimbabwe its independence in 1980, the school began admitting select sons of the country's new Black centre classes, like me. When I passed the exacting admissions exam – iv papers, in maths and English, notoriously difficult to complete – I felt, in my juvenile way, that I had earned my place in the world. Only when I arrived, in January 1999, I was suddenly afloat in a Republic of zimbabwe unlike any I had known before.

At 7.25am on my showtime 24-hour interval, the school bell rang, and I joined the other boys in their red blazers filing into the Beit Hall. The hall was named after an Anglo-German gold and diamond magnate who employed Rhodes when the latter start arrived in southern Africa. Every bit I glanced upwards to an interior balcony, I noticed a series of polished mahogany panels with golden lettering bearing the names of Old Georgians who had won the Rhodes scholarship, which sends about 100 international graduates to study at Oxford every year. I could see that near of the names belonged to white students.

During the assembly, new pupils were informed that we had a two-week grace period in which to main the higher's peculiar traditions and hierarchies. We would then be tested on school history and expected to follow local custom to a T. Over the grace period, I anxiously crammed the college mottoes, the names of all the prefects and captains of sports, the history of the founding fathers and the first six pupils to nourish the college, the numbers of One-time Georgians who had died in the offset and second earth wars. At Saints, this was the past that seemed to matter most.

Discipline was of import, too. I quickly learned to live in fear of the prefects, senior boys entrusted with meting out punishments for even the almost minor transgressions. A careless misstep could issue in transmission labour – a routine penalty where we had to dig fields and comport bricks for hours in the heat of an unforgiving sun. Even worse was the threat of beingness sent to the headmaster for "cuts". I imagined the headmaster's cane whipping across my tender buttocks, raising a fine welt of swollen tissue. No, give thanks you.

Saints'southward rituals of say-so and sadism were just some of the ways that it taught its boys to have the logic of colonialism. Wasn't it only natural that older students ought to wield power over younger ones, or that those who excelled at sports or schoolwork be granted privileges, similar the ability to tread on certain college lawns, that were denied to bottom children? Wasn't it right that those who stepped out of line be forced to labour, or even whipped? These were perfect lessons for a world in which ane race thought itself worthy of violently subjugating another. Later on independence, Saints'south ways were embraced by a Black middle class that had imbibed colonial culture and internalised that culture'due south sense of superiority.

For my parents, the decision to ship me to this old imperial preparation ground was a fraught i. My female parent was a women's rights advocate, built-in in 1957 to a big working-class family in what was then the British Protectorate of Republic of uganda. My father, born six years earlier, grew up under the full weight of racial segregation in Rhodesia, where 250,000 white people, barely 3% of the population, had usurped more one-half of the state's agronomical land and owned near all of its commerce and industry. Black people were denied the franchise, their movements were controlled by a punitive internal passport system, and they died at heinous rates from chronic malnutrition, high infant mortality and express access to basic wellness services. Meanwhile, white people in Rhodesia enjoyed the highest per capita number of private swimming pools anywhere in the earth.

Radicalised by the condition of Blackness people, my father fought against the Rhodesian regime in the liberation war that began in the early 60s. During the disharmonize, my uncles and an aunt were incarcerated by the Rhodesian country, my father was well-nigh killed on the battlegrounds bordering Zimbabwe and Mozambique, and my granddad was lynched past Rhodesian security officers.

Following independence, my father joined Zimbabwe's ceremonious service, and he and my mother began a suburban life that was small-scale in means but not in aspiration for their son. St George's appealed to them, as it did to many Black families like ours, because of the cultural and social foothold it provided. Boys from Saints regularly went on to study at Oxford, or play on Republic of zimbabwe's historic national cricket team. But inside the cloistered world of the college, the war of independence my male parent fought seemed to be only half-complete.

Formal segregation in Zimbabwe had concluded about two decades before, simply even in 1999 the higher signalled its prestige through its racial makeup. We had a white headmaster and a white rector. The teachers with the strongest reputations for excellence were white. We also had a loftier pct of white students, well-nigh half of the educatee body in a country where white people made upwards less than 1% of the population.

Without quite realising it, this was a racial logic I readily accepted. In his memoir of growing upward white in Africa, the Zimbabwean author Peter Godwin recalls meeting a handful of Black students at Saints in the 60s: "They didn't want to talk over African things. They wanted to exist similar whites. They spoke English without much of an African accent." I suppose I was much the same. I barely spoke Shona, the linguistic communication my father was raised speaking, merely had a fluent command of English. I resented white racism merely aspired to the cultural capital of whiteness.

It was obvious, though, how bourgeois white Zimbabweans – "Rhodies", Blackness people call them – saw me, whether I wore Saints'southward red blazer or not. "Chigudu," 1 white classmate said to me, "what's the difference between a nigger and a bucket of shit?" I looked at him blankly. "The bucket," he chortled.

Early on, I committed myself to the art of survival at Saints: mine was a two-pronged strategy of conforming to expectations and never questioning dominance. I kept a low contour throughout my first year, maintaining a steady, mediocre functioning in all aspects of school life. My mother worried I might cede any talents I had to this strategy, and urged me to be more than ambitious. I took heed and, around the fourth dimension I turned xiv, I started to apply myself seriously in my studies. I refused to be defeated past Thomas Hardy's dense prose, I agonised over the difference betwixt ionic and covalent bonds, I memorised Latin noun declensions. I began to excel academically, and found the success intoxicating. Merely as I grew in enthusiasm for Saints, I failed to notice another way that colonialism was still operating at the college: we were learning almost nothing about the troubled country that lay across those black gates.

I gnorance of history serves many ends. Sometimes it papers over the crimes of the present by attributing too much ability to the past. Peradventure more frequently, it covers up past crimes in lodge to legitimise the mode society is arranged in the present. Equally a teenager, I saw these dynamics play out in the former colony of Rhodesia. I would later find how much more potent they were in Britain, the metropole.

By the turn of the millennium, outside the walled-off kingdom of Saints, Republic of zimbabwe'southward colonial legacy was unfolding in dramatic and fierce means. Although formal segregation had concluded in 1980, the world that apartheid built had never fully ceased. Past the beginning of my second twelvemonth, the country was descending into what would soon be called "the crisis".

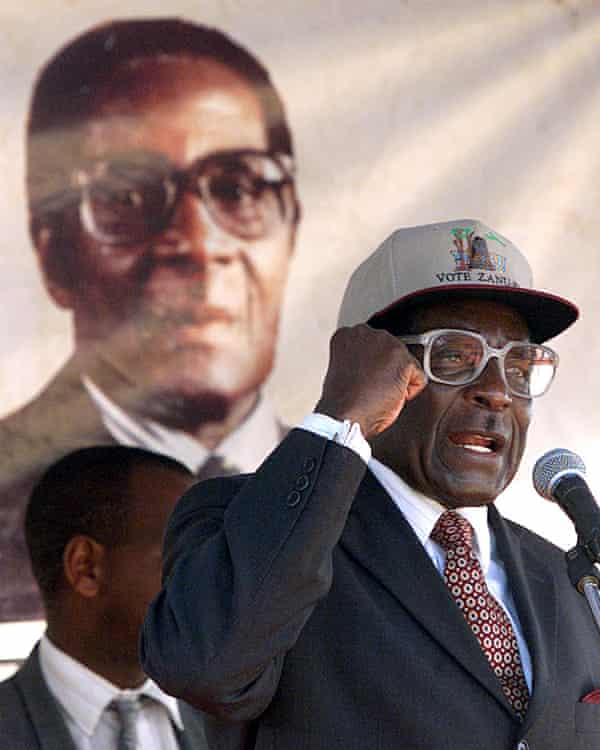

Throughout the 90s, the government of Robert Mugabe, who had been in power since independence, had lost popular support. Corruption, economic austerity, the land's involvement in a state of war in the Democratic republic of the congo, and a failure to fully accost the primal problem of who owned Zimbabwe's land – white settlers or Black Africans – all threatened Mugabe's power. A new political political party arose that claimed to stand up against Mugabe and for the values of democracy and civil rights.

Mugabe responded by blaming all of Zimbabwe's problems on its history of colonialism. And no figure was more foundational to that history than Cecil Rhodes. In 1877, Rhodes chosen for the British, "the finest race in the world", to rehabilitate "the most despicable of human beings" by bringing them under British rule. Two decades later, he paid for the conquest of Rhodesia with the profits he had extracted from Black labourers in his Southward African golden and diamond mines. After seizing land from Africans, Rhodes's British S Africa Company forced them to toil on information technology as indentured labourers. As one early biographer put it, Rhodes "used blacks ruthlessly … giving them wages that fabricated them little better than slaves". This was the footing for the apartheid regime that existed in Rhodesia until political independence.

It was true that Rhodes was a racist and imperialist who congenital a society based on racism and exploitation. Just Mugabe used this history to deny the corruption of his ain government. He fabricated white farmers the scapegoats for the country's economic problems and tarred the opposition as un-African. He argued that the values his political rivals stood for were a encompass for neoliberal policies that, similar colonialism before them, would only serve to exploit Zimbabwe on behalf of the w. Real nationalism, Mugabe said, was nearly finishing the anti-colonial liberation struggle by taking back the land.

In 2000, bolstered past Mugabe'due south rhetoric, Black war veterans began occupying commercial farmland owned by white people. The occupations spread widely beyond the country. They were sponsored by the ruling political party, while partisan militias carried out evictions on the basis. In less than v years, the number of white farmers actually farming the land dwindled from well-nigh 4,500 to under 500, while equally many equally 200,000 Black farm workers lost their jobs, and often with them their homes. About 10 white farmers were killed by militias, while the number of black farm workers killed by the aforementioned militias was merely nether 200, with many thousands more than suffering violent assaults.

The foreign and white media soon introduced its ain distortions into the crisis, portraying the occupations as a racially motivated assail against white people, and not as a violent political uprising rooted in the complex history of colonialism. At dwelling house, my father praised Mugabe and lambasted western powers as hypocrites who preached democracy but practised imperialism. He had no patience for the opposition party, whose members he saw as stooges serving the interests of white capitalists in Republic of zimbabwe and Great britain. I later came to encounter the land seizures as acts of political and economic grievance that answered direct to Republic of zimbabwe's colonial history, and to feel that, in many ways, Mugabe and my father were right: existent emancipation from that history could non be accomplished if white people still owned more than than their share of the land.

At the time, though, I accepted their arguments in office because I connected the aims of the land struggle with my distaste for the racist Rhodies I was surrounded past at Saints. Merely and then Mugabe took aim at schools. He argued Saints and its ilk represented a refusal of former colonisers to fully acquiesce to African leadership (once more, not entirely wrong). His Ministry of Teaching attempted to implement a state-controlled curriculum that would teach Mugabe'due south version of history. I panicked. I was supportive of decolonisation if it concluded with farms, but schools were another matter. I worried that I would be forced to sit local exams that lacked the credibility to earn me university admission overseas. The idea of going to university in Africa had non even occurred to me.

The educational reforms I dreaded had not come to pass in private schools by the time I completed my O-levels in 2002, but Republic of zimbabwe was facing economic and political meltdown. Sanctions were before long imposed on the land and Mugabe was condemned past western governments, the media and NGOs for human rights violations. My comprehension of "the crisis" was rudimentary, but I saw its effects in my daily life. Even in the wealthy bubble of Saints, textbooks and chemistry sets were all of a sudden in short supply. Aggrandizement and therefore schoolhouse fees spiralled out of control, forcing staff and students to leave the college in droves. The headmaster was arrested after accusing Mugabe, in racist terms, of rigging that yr's election.

Though my parents believed in redressing the colonial theft of African land, like many other Black parents of their class, they recognised that their children would have better educational opportunities exterior Zimbabwe. So in 2003, I joined a wave of young Zimbabweans emigrating for pedagogy abroad. My mother travelled with me to England and deposited me at Stonyhurst Higher, a 400-year-quondam Jesuit boarding school in rural Lancashire on which much of Saints'due south compages and pedagogy had been based. She cried all the way downwardly the school's near mile-long driveway.

I t wasn't until arriving in England that I began to appreciate that colonialism had furnished not just Zimbabwe but Britain, too, with fiercely held national mythologies. In both countries, colonialism had left behind ideas and institutions that stood in the way of a more honest reckoning with the past.

At Stonyhurst, I felt like I had stepped out of Saints'south pantomime version of English boarding schools and into the real matter. But I was taken aback by the view of Zimbabwe I soon encountered. If Mugabe liked to claim that colonialism was the cause of all the country'southward problems, many of my new classmates were equally simplistic in blaming them entirely on Mugabe. One even suggested that recolonising Zimbabwe might finish its woes. To a large extent, they were parroting the British and international media, which portrayed Mugabe equally an icon of evil fixated on murdering white people. Even Hi! mag devoted a v-page special on Zimbabwe to covering the death of a white farmer. Little to nothing was said, in the media or elsewhere, of Republic of zimbabwe's colonial legacy, or of the suffering of Black people under Mugabe's government.

At the same fourth dimension, it was dawning on me how picayune I myself knew almost my own country. I began to read more about Zimbabwe's history, and was startled by what I plant. In particular, I had known nil nigh the Gukurahundi massacres perpetrated by the state following the state of war of liberation. In the worst case, as many every bit twenty,000 civilians from the Ndebele people were murdered past the Zimbabwean regular army over a menstruum of 5 years in the mid-80s. It was a double shock: not but at the size of the atrocity, but at the telescopic of the ignorance I had been encouraged into at home and at school.

Having once been proud of my success at Saints, I was suddenly ashamed at how sheltered and privileged my life had been. Motivated by an uneasy combination of guilt, idealism and a longing for home, I resolved to get a doctor and get dorsum to Zimbabwe to help heal the nation. After finishing at Stonyhurst I took up a place at Newcastle University to report medicine. I was one of very few Black faces in the medical school, and the only i from continental Africa. Racism was no less mutual than it had been at Saints, but information technology took a variety of forms. Sometimes it was direct: I was chosen a "golliwog" by patients while on clinical rotation and told to "fuck off dorsum to Africa" on nights out in Newcastle urban center centre. More often, it was subtle and patronising: white students touched my hair without my consent or expressed incredulity at the eloquence of my spoken English language. One fifty-fifty called me "the whitest Black man I know".

The more my white friends made it clear that I didn't fit their notions of what it meant to be Black or African, the more I, too, questioned the authenticity of my Blackness. At the same fourth dimension, in Republic of zimbabwe, people like me were cast as sellouts who preferred their former coloniser to the motherland. I felt as if I was losing my grip on who I was. For a while I sustained myself with my fantasy of returning dwelling to treat the ill. But, as Zimbabwe's crisis grew larger and larger, my clinical training felt inadequate. Dorsum home, inflation was out of control. On a visit in 2008, I bought an ice-cream sundae in a Harare suburb for 38 billion Zimbabwe dollars. Public services, including healthcare and sanitation, had largely disintegrated. Major shortages of basic commodities – such as fuel, cooking oil, staff of life and h2o – compounded the effects of political turmoil and violence. Cholera was competing for lives with one of the highest HIV rates in the world.

By the fourth dimension I qualified as a doctor in 2010, I regularly spent my quiet nighttime shifts in the infirmary reading books about Zimbabwe and Africa. Nearly of the ones I could find in local bookshops were accounts past western journalists and memoirists who decried aspects of colonialism but thought African politics was ineluctably despotic. In light of what Mugabe had done to Zimbabwe, many of these authors argued, maybe colonialism wasn't that bad.

Not everything they said about colonialism or Mugabe or Africa was entirely wrong, but little of it struck me as entirely right either. In a sense, I was shedding the world and the worldview I had been inducted into at Saints, only I wasn't quite sure what I should supplant it with. Once again, I felt at sea. I decided to commit myself to studying African history and politics, in the hopes not necessarily of helping my country, merely but of better understanding information technology. After three years of practising medicine, I left the NHS and took up a scholarship at the University of Oxford, where I in one case over again found myself directly in the shadow of Cecil Rhodes.

W hen I arrived at Oxford in the autumn of 2013, I was surprised to notice the ghosts of Republic of zimbabwe's colonial past all around me. None haunted the place more Rhodes, who had been a student at Oriel college in the 1870s, and later gave millions to the university through a number of gifts and bequests. Nearly striking of these to me was Rhodes House in fundamental Oxford, a gathering place for recipients of the scholarship. (To my smashing unease, the Rhodes scholars I met often referred to themselves with the same term Blackness Zimbabweans refer to racist white people – "Rhodies".) Rhodes Firm is a grand building in the style of a Cotswold manor, with one clearly incongruous feature: on top of the edifice's copper-clad dome perches an enormous bronze carving that I recognised immediately – the Zimbabwe Bird.

The sculpture is a copy of 1 of a one-half dozen or so 11th-century carvings stolen in the late 19th century from the aboriginal city known as Great Republic of zimbabwe, in the state's south-eastern hills. Rhodes believed the sculptures too sophisticated to have been fashioned by an African culture, and attributed them instead to a Mediterranean civilisation. In fourth dimension, I came to see the carving atop Rhodes house as the negative image of what would soon become a much more than famous statue: a larger-than-life likeness of Rhodes that peers down on to Oxford'due south High Street from a niche high up Oriel college's facade, above a Latin inscription thanking him for his munificence. If the statue of Rhodes portrayed him as a nifty benefactor, the Zimbabwe bird stood for the wealth extraction and human exploitation on which Rhodes's fortune was built, as well as for the racist ideology that helped him justify his colonial programme.

Colonialism connected to shape Oxford in less physical ways, too. I wasn't at that place long before I learned that the dim view of Africa and Africans held by Rhodes had been shared by many of Oxford's most esteemed historians. Hugh Trevor-Roper, who for a quarter century held Oxford'south most prestigious history chair, infamously pronounced in the 60s that there was no African history, "but the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness." Before Europeans brought history to Africa and places like it, Trevor-Roper went on, there was only "the unedifying gyrations of cruel tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe". This was simply a touch on crasser than what a Beau at Balliol College said to me at a dinner in my 2nd yr at Oxford: "African politics? What a mess. How could you lot peradventure prepare that?"

Among the handful of Oxford scholars who actually studied Africa, however, nearly had a nuanced understanding of the continent and shared my disgust at Rhodes. William Beinart, who was then the Rhodes Professor of race relations, quipped that his title was an embarrassment, like having the position "Goebbels Professorship of Communication". Just although my professors at the African Studies Centre were rigorous scholars, I couldn't help but notice that they were all white. This is true throughout academia: at that place aren't a massive number of Blackness people in the U.k. – simply almost 3.3% of the population – merely in that location are far fewer Black academic faculty (almost two%) and about 140 Black professors in the whole state.

My studies and my family unit's history every bit colonial subjects came together most painfully in a seminar on the history of political imprisonment and punishment in Africa. My father had told me petty almost his incarceration in a Rhodesian prison during the liberation war, except to say that the atmospheric condition were "inhuman" and that the prison guards caned his buttocks so desperately that they streamed with blood and he couldn't sit for weeks. Now, in Oxford, I spent every Friday morning in a sterile seminar room where Prof Jocelyn Alexander guided my classmates and me through a discussion about how colonial states – most dramatically, settler states similar Rhodesia – employed corporal and capital penalisation, mass incarceration and labour detention on a large scale equally a means of creating social society in Africa and shoring upwards white political domination.

Of course, white domination and colonialism wasn't just something that happened in or to the colonies. The more than time I spent in Oxford, the more than I realised how colonialism had remade the entire material and intellectual world of the British empire, especially its most aristocracy academy. Oxford is strewn with tributes to men of empire who have scholarships, portraits, busts, engravings, statues, libraries and even buildings dedicated to their memory. Christopher Codrington, a slave plantation possessor, bequeathed £one.2m in today's money to All Souls College to erect i of the university'southward most magnificent libraries (which, until final year, bore his name). George Curzon, the viceroy of Republic of india who presided over the Indian famine of 1899-1900 in which well-nigh 4 million people died, is memorialised at his alma mater, Balliol. Augustus Pitt Rivers, a 19th-century colonial officer, founded Oxford's archaeological museum, which long doubled upwardly as a storage facility for loot stolen during the British empire.

From the start, the quest for knowledge of Africa was motivated by the aim of conquest. Even today, African studies has an air of the 1884 Berlin Conference, which heralded the "Scramble for Africa" – simply instead of European powers claiming and trading dissimilar parts of the continent, it's mostly white scholars staking out their territory and asserting expertise over ethnicity in Kenya, democracy in Republic of ghana or refugees in Uganda. Later I stayed on at Oxford to pursue a doctorate, I began attention African studies conferences throughout the Britain, only to find mostly white scholars talking to predominantly white audiences.

In other words, I was surrounded in Oxford not by the ghosts of colonialism, merely past its living expressionless. As at Saints, colonialism at Oxford had never really ended, and couldn't. It wasn't a period that had passed, only a historical mass that bent everything around its gravity. Equally I had in Newcastle, I began to question the strange identify I occupied in this contorted globe. Every mean solar day, I left Africa more completely, while becoming more intimately involved with the colonial project that the academy represented. In a sense, I was complicit in that project – but I was also alienated and angered past it. I was at a loss about how to navigate the ambiguities of my position.

Then, on ix March 2015, a student at the University of Cape Town hurled a bucket of human shit at a statue of Cecil Rhodes. All of a sudden, everything that I and many of my fellow Black students had been feeling near Oxford came into precipitous focus. A movement to redress the colonial legacy of neglecting and denigrating Black students was afoot in Due south Africa. Before I knew information technology, I would become a leader in a fight to remake Oxford, too.

W e called our work decolonisation. In that location were several dozen of united states of america – Black and brown students who were born in Britain or its old colonies, African American students who saw links between decolonial politics and anti-racism piece of work in the The states, and a number of white students. Our goal was to slay the racist ideologies that still held sway in various disciplines, to bring more Blackness people into academia at every level, and to end the glorification of the men who had defended their lives to advancing the colonial project. The scale of these ambitions was core to our politics. We were non interested in half measures or compromises with institutional racism. We knew it would exist an uphill boxing. Every bit one of my friends cautioned me, "Y'all know what they say near Oxford, Simukai? 'Change is skilful. But no change is amend.'"

To draw attention to the fight, we decided to focus on a single object, the statue of Rhodes on Oriel college's facade, borrowing the name of the student movement in S Africa: Rhodes Must Fall. I had originally opposed this tactic, worrying that focusing on the statue would obscure our larger mission. Merely my friend and young man organiser Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh eventually convinced me that the fight over the statue would be an important litmus test, revealing merely how committed – or resistant – the university and its various members were to catastrophe racism in all its forms.

The first activity of Rhodes Must Autumn in Oxford was to protestation a debate at the Oxford Marriage Guild on the legacy of colonialism in May 2015. We wanted to press the point that colonialism was not a affair of the past. When nosotros arrived at the argue, we discovered to our astonishment that the Marriage had inadvertently browbeaten us to the punch: the bar was ad a cocktail called the "Colonial Comeback" with a flyer depicting Blackness hands in manacles. Racist attitudes were obviously alive and well. We posted photos of the flyer to social media, and they shortly went viral, prompting national outrage.

A few months afterward, in Nov, Rhodes Must Fall organised a 300-person strong protest outside Oriel higher. Ten times that number had signed a petition demanding that the statue of Rhodes exist taken down and housed in a museum. Protesters condemned the statue equally "an open up glorification of the racist and bloody project of British colonialism", and people chanted in call-and-response, "Rhodes Must Fall! Take it Downward!".

I tracked the protest from Harare, where I was researching my PhD, gathering harrowing testimonies from human rights activists, politicians and the urban poor about how they had suffered during the country's 2008 cholera outbreak, in which 100,000 people were infected and more than iv,000 people died. I wanted to empathize how a simple bacterial infection became a public health disaster and a political scandal in a country that one time boasted the best healthcare organization in Africa. Countless western critics laid the arraign for this crisis at the anxiety of Robert Mugabe. Mugabe's government hitting dorsum with an absurd counternarrative claiming that the cholera outbreak was racist, terrorist, biological warfare from the west to undermine African sovereignty. I asked one medico, a friend of mine from Saints, whether he believed in the government'south anti-colonial rhetoric. "I am anti-colonial and anti-neo-colonial," he said, ruefully. "I know that Swell United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland is wealthy in part because it has plundered countries similar ours. Nevertheless, our leadership has failed usa."

When I returned to Oxford in January 2016, I began debating Rhodes Must Fall at student society meetings, colleges, other universities and in the press. Were we historically illiterate, attempting, as some of our opponents ironically charged, to "whitewash" history? Different many of our critics, we at least recognised that the statue of Rhodes did non really be in the past. It is not a sterile historical relic, or some accurate record of prior events. Information technology is a piece of cocky-conscious propaganda designed to present an ennobled image of Rhodes for as long every bit information technology stands. (Mugabe was using a similar strategy when he tried to rewrite Zimbabwean history.) If anyone was trying to erase the past – specifically the history of subjugation and suffering on which his fortune was built – information technology was Rhodes. I had to wonder why many eminent white commentators were so attached to him.

The ultimate signal was never to weigh the soul of Rhodes, and observe out whether he was "really" a racist. It was to try to uproot the racism in the soul of the institutions built in his prototype. It was apparent that many of our critics, even some of those who knew something nigh colonial history, couldn't appreciate how Rhodes and the colonial project had intimately shaped lives like mine. They couldn't fathom the ways in which colonialism had never really concluded.

As a collective, nosotros idea we were making progress on our aims when Oriel College pledged to launch a six-month listening exercise to gather show and opinions to help decide on the future of the statue. But, a mere six weeks later on, in late January 2016, the college reneged on this pledge, stating that it would not remove the statue of the imperialist on the grounds that there was "overwhelming" support to proceed it. Information technology was later revealed Oriel stood to lose £100m in donor gifts were information technology to take downwardly the statue. I was crushed, and for a long time it seemed like Rhodes Must Fall had failed.

F our years later, in May 2020, I sabbatum alone in my flat in Oxford watching the video of the brutal torture and murder of George Floyd at the knee of constabulary officer Derek Chauvin. Later my shock came ache and rage. For days on end, I consumed the news and commentary on the killing, until my mind was foggy and my body ached. I can't tell you if I thought about my begetter's father, who was murdered by the Rhodesian country before I was born, but I know that, similar many Black people, I experienced Floyd'due south death as an intimate and personal trauma. If you have ever been on the abrupt end of anti-Blackness racism, it is not difficult to identify with the suffering of other Black people under all kinds of racist regimes.

Ten days later on Floyd's death, the heads of all the Oxford colleges – every single one of them white – wrote an open alphabetic character in the Guardian claiming that they stood in solidarity with Black students and affirming their commitment to equal nobility and respect. I immediately idea of Gary Younge'south piercing observation that white people periodically "detect" racism "the same way that teenagers discover sex: urgently, earnestly, voraciously and carelessly, with dandy cocky-indulgence simply precious piddling cocky-awareness."

It had been four years since Rhodes Must Fall had seemingly dissipated. There had been a few pocket-size changes at the university – Hugh Trevor-Roper's proper name was stripped from a room in the history kinesthesia – and at least one more substantive reversal: the Pitt Rivers Museum began repatriating some of its stolen works. (Dan Hicks, one of the museum's curators, has since written that Rhodes Must Fall "shattered the complacency" at the institution.) But the primary aims of our piece of work had not been far advanced, and the statue of Rhodes still stood.

I had remained in Oxford, completing my doctorate before being appointed to the faculty every bit an associate professor of African politics. As one of the few people from the first wave of Rhodes Must Fall who was notwithstanding at the university, I was asked to speak at an antiracism protest on 9 June. I stood before a crowd of thousands gathered on Oxford'south loftier street exterior Oriel College, beneath the Rhodes statue. As soon as I took the microphone, the words "Rhodes Must Fall!" came out of my rima oris with a guttural force that I couldn't contain. The oversupply responded with thundering applause.

On 17 June, Oriel Higher'south governing body expressed its wish to remove both the Cecil John Rhodes statue and a plaque commemorating him. To implement this, the college launched an contained Committee of Research tasked with because the Rhodes legacy and wider concerns most inclusivity, access and experiences of Black and other minority ethnic students at the college. A formal conclusion to remove the statue is expected later this year. Meanwhile, All Souls College removed the slaver Christopher Codrington's name from its iconic library, and University College appointed the beginning Black head of a college in university history, Valerie Amos. Progress is slow, and never inevitable, but it tin visit fifty-fifty Oxford.

I am frequently asked how I experience well-nigh beingness an associate professor at Oxford, specialising in African politics. Do I come across any contradiction in working for the institution that I am agitating to change? Who is the target audience of my writing – privileged, often white students, or my fellow Africans? The answers to such questions are long. Even so, there's a fallacy in thinking that Africa is where I am needed most. Yes, I remain committed to writing about the flammable politics of the country of my birth, and I hope the true promises of liberation will be fully realised one day. But Oxford, Britain, and the west must be decolonised, as well. Essential to this is advancing a richer, more complex view of the majestic by and its bearing on the present. Zimbabwe is not U.k.'s troubled sometime colony – it is its mirror. Every bit the corking Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe humbly put information technology: "I would suggest from my privileged position in African and western culture some advantages the West might derive from Africa once it rid its heed of old prejudices and began to look at Africa not through a haze of distortions and inexpensive mystification but quite simply every bit a continent of people – non angels but not rudimentary souls either."

This commodity was amended on fifteen January 2021 to clarify details of Rhodes' financial gifts to the Academy of Oxford, which amounted to millions and not £100,000 as an earlier version said. The latter sum was Rhodes's donation to Oriel college specifically. Too, the Zimbabwe Bird on the dome of Rhodes Firm is made from bronze, not soapstone.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jan/14/rhodes-must-fall-oxford-colonialism-zimbabwe-simukai-chigudu

0 Response to "People Who Want Zimbabwe to Become Rhodesia Again"

Post a Comment